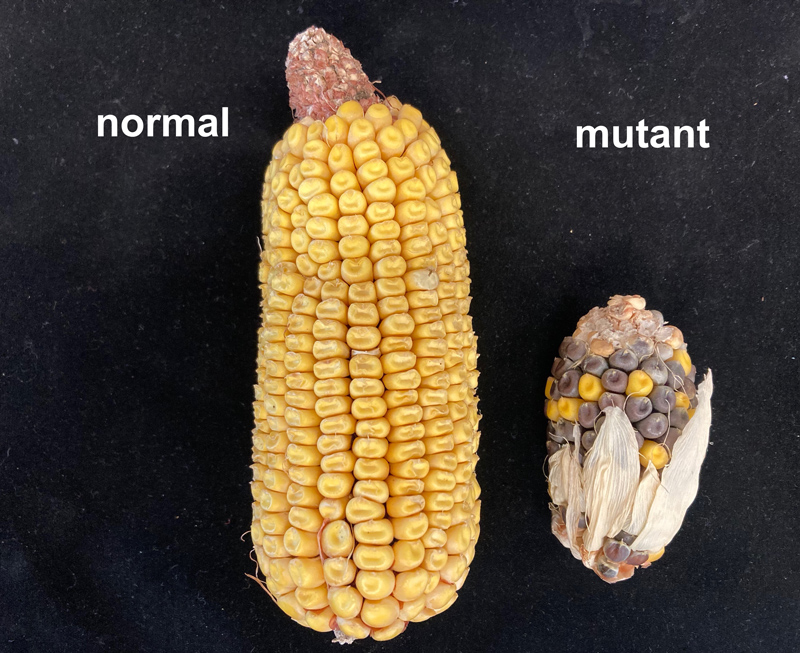

The tasselsheath4 mutant (right) displays traits found in the wild ancestor of maize.

A new study published this week in Nature Genetics sheds light on the mechanisms underlying the domestication of maize, providing valuable insights into the complex genetic network that helped transform it from an inedible weed into a staple food for communities and cultures across the world.

Nearly 10,000 years ago, farmers began the process of selecting specific traits in wild teosinte grasses—like larger seeds or more favorable growth patterns—to make them more amenable to agriculture. Generations of selective breeding helped give rise to the high-yielding maize crop of today, but scientists had yet to fully identify the genes responsible for these traits.

Using high-throughput genomic techniques, a team led by Department of Plant and Microbial Biology researchers Zhaobin Dong and George Chuck has uncovered tasselsheath4 (tsh4), a maize domestication gene that sits on top of a large regulatory network that controls numerous agronomically important traits. Specifically, the authors found that tsh4 targets and regulates a suite of downstream genes involved in crucial developmental processes, including the formation of boundaries between different cell types, the suppression of leaf growth, and the promotion of axillary meristem growth.

“The identification of this new gene will give geneticists and breeders the blueprint to domesticate more resilient grass crops better suited to withstand climate change,” said Chuck, who is also a researcher at the Plant Gene Expression Center in Albany.

Additional UC Berkeley co-authors include postdoctoral researcher Elena Shemyakina, undergraduate alum Geeyun Chau (BA ’21 Molecular and Cellular Biology), and adjunct professor Jennifer Fletcher. Researchers from China Agricultural University, Brigham Young University, and North Carolina State University also contributed to the study.

Read more